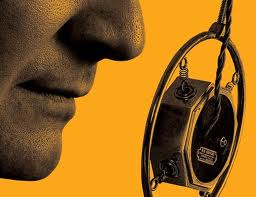

We observe also that the scope of the voice is far greater than that of language. If the human voice is particularly effective as a means of communication, it is also very affective. Depending as it does on breath, it comes from within the speaker’s very body, and is an amazingly versatile instrument with enormous capacities for producing a vast range of sounds. There are a great variety of ways in which the voice can be manipulated to express the different emotions that the speaker experiences; much can be ‘said’, in addition to the words used, by the tone of voice employed. If ‘yes’ in the English language means that the speaker’s consent is given, there are numerous ways in which, with his voice, the speaker can express the way in which he gives his consent: wholeheartedly, hesitatingly, reluctantly, etc. Thanks to language, thought and intention may be expressed and communicated, but the voice has a special role in communicating the way in which I relate myself to something – to the object under discussion, to the idea presented, and ultimately to the person with whom I am speaking. It will be the way in which the ‘I love you’ is expressed with the voice that will ‘say’ the quality of that love, that will tell the friend something about the way in which he is loved. We may say, perhaps, that if it is the intelligence that dominates sound in language, it is the will in its capacity to love that masters sound to express itself in the voice.

With man we also reach a level of gratuity in sound that goes beyond even communication using language. Just as man enjoys listening to sounds, so too he enjoys using his ability to make sound without necessity, for no particular reason. This is indeed where we find music. In whistling or humming a tune, even in singing itself, man uses his ability to make sound for more than its primary and basic functions, for the pure joy of doing so, and this thanks to his intelligence and life of the spirit. (Some people would argue that birdsong is also at this level of pure gratuity, but is that really true, or is it an imaginative projection of our own experience? Perhaps the key to this will be melody, which we shall consider later.)

We start to see also, therefore, how sound’s capacity to be the vehicle of meaning, thanks to language and the human voice, has something to do with music’s power to affect the emotions. Sound is the privileged medium for conveying meaning. Meaning is also conveyed through the other senses of touch and sight (we think, for example, of the tenderness expressed in a touch, or the anger expressed in a look), but mutual understanding and communication are possible in a special way thanks to the sense of hearing and the conventions implied in language. As receiving the sound of a reality makes me aware of its presence, its position and distance in relation to me, by the sounds I myself make with the instrument of the voice, I express my reaction or attitude to that reality – the emotion or passion which that reality and its distance or position in relation to me give rise to. But we must also bear in mind that language has its limits; we cannot express every emotion we experience in words. Vocal expressions that do not involve language may sometimes convey more than language is capable of expressing; we might think of a sigh, for example. But even such non-verbal vocal expressions as this are not always adequate to the expression of emotions. In a sense, language and the voice as a means of communication culminate in a silence; in the silence of a pain too great to speak of, in a compassionate silence, in a loving silence. This silence is again, particular to man. The physical world, being in constant movement, is never silent; the living world has periods of silence, but it is only with man that silence is willed. Movement, and so sound, can be most fully dominated, mastered, by man. Indeed, man’s ability to control both the movement of his breathing and the movement of his touch will be essential elements when it comes to music.

So much, then, for the different types of sound, culminating with the silence of man; we move on now to consider more closely what sound itself is. We can distinguish three, as it were, aspects to a sound; its pitch, its volume and its proper character – what we might call its timbre. We shall consider each of these in turn.

De Broeders van Sint Jan hebben hun leven aan God gewijd, ten dienste van God en hun naasten. Zij willen leven volgens het Evangelie van Jezus Christus en zich door hun gebed en hun activiteiten inzetten voor jong en oud.

De Broeders van Sint Jan hebben hun leven aan God gewijd, ten dienste van God en hun naasten. Zij willen leven volgens het Evangelie van Jezus Christus en zich door hun gebed en hun activiteiten inzetten voor jong en oud.